WASHINGTON, KOMPAS.com - While the past year’s battle with COVID-19 has been grueling for health care workers across America, the challenge has been compounded for Asian medical professionals, who have also had to work amid a wave of pandemic-inspired anti-Asian attacks.

“The past year, it was just so many different mixed emotions between the pandemic... [and] issues? regarding? racial ?injustice. All that put together made last year very different from other years,” said Austin Chiang, a doctor whose parents emigrated from Taiwan to the U.S. 10 years before he was born in Irvine, California.

On the same day that six Asian American women were slain with two other individuals in Atlanta last week, the advocacy group Stop AAPI Hate released a report that cited 3,795 hate incidents targeting Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders between March 19, 2020, and Feb. 28, 2021.

More than 500 of the incidents were recorded since the beginning of this year.

COVID-19 was first detected in humans in Wuhan, China, in late 2019. Spreading globally since then, it has felled more than 548,000 people in the U.S., where there have been more than 30 million confirmed cases, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

Not gonna lie — given recent events, I walked a little faster to get home and avoided eye contact with anyone. #StopAsianHateCrimes

— Austin Chiang, MD MPH (@AustinChiangMD) March 17, 2021

In 16 of the most populous U.S. cities, attacks on Asian Americans increased in 2020 by almost 150% over the previous year, according to data compiled by California State University’s Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism.

That has made the past year a time of reflection for Chiang, who holds a master’s degree in public health from Harvard University and an M.D. from Columbia University.

He has been active on social media countering COVID-19 misinformation?as the chief medical social media officer for 14 hospitals operated by Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and founder of the Association for Healthcare Social Media (AHSM).

The death of George Floyd, an African American man who died while in police custody in May in Minnesota, and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, “made me rethink a lot of things about ways we can try to incorporate equity around my workplace and making sure that others feel like they are treated fairly and are seen and heard,” the gastroenterologist told VOA Mandarin.

“It’s definitely been jarring and a bit hard to reconcile because at the same time feeling … we’re being judged not for our skill but for our appearance, and certainly that’s something that affects so many different people.”

“The funniest thing was a Caucasian gentleman called me, like, ‘Eggrolls,’” said Vannthath Man, 42, of Haymarket, Virginia, an ICU nurse at Inova Fairfax Hospital who studied nursing at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia.

Also read: 2 Indonesian Citizens Fall Victim to Racial Abuse in the US

“I don't take these things personally … He may have that thought in the back of his mind but if he was not medicated, if he was not confused, he would not have said it. But it doesn't make him right to think that way.”

Born in Battambang, Cambodia, Man was bullied to tears and outcast during his first years of school after he arrived in the U.S. in 1989 at the age of 12 with his family.

At the time, Man told VOA Khmer he thought “it might be a good idea if someone were to help …maybe I wouldn't have the suicidal thoughts, maybe I didn't have to go through such a hard time. So that's why I went into the help industry or (became) a nurse because I want to help people.”

On a day when four of his six COVID-19 patients died in the ICU, Man turned to the self-care methods created for himself as a teen.

“Culturally, our family (was) not very open on talking about certain things. … A lot of time (I dealt) with things by myself. … So with that day, I thought … about what positive attributes you have, what positive things you give to the community.”

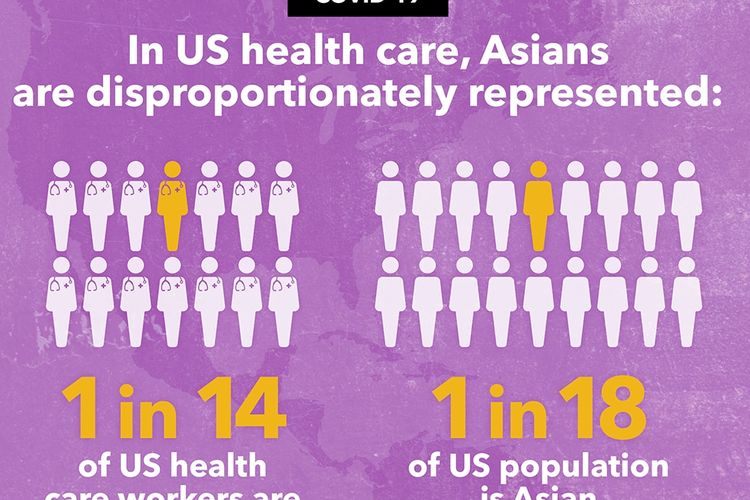

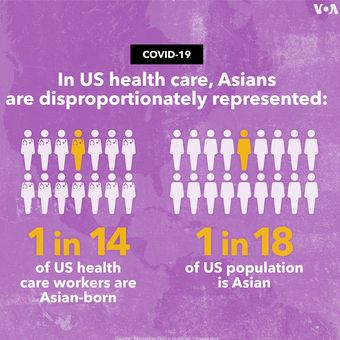

Asians, U.S.- and Asian-born combined, are disproportionately represented in health care given their numbers in the overall population, according to figures from the Migration Policy Institute and the U.S. Census.

Proportion of Asians in US heath care

Proportion of Asians in US heath careOf the foreign-born health care workers in the U.S., 40% come from Asia.

40% of health care workers in the US come from Asia

40% of health care workers in the US come from AsiaAdam Conners, 35, is a native of Malang, East Java in Indonesia. He arrived in the U.S. in 2011 for a visit with friends.

He collapsed with seizures brought on by late-stage tuberculosis and spent three months in George Washington University Hospital in Washington, D.C., where the nurses delivered his treatment with such care he decided to join their ranks.

After learning English, he enrolled in an accelerated nursing program at Chamberlain University in Downers Grove, Illinois, condensing four years of study into 30 months. He graduated in 2017 with a bachelor’s degree.

“It was tough,” Conners told VOA Indonesia of his intense program. Now an ICU nurse in the hospital where he returned to health, he treats African Americans,?Hispanics,?Asians, Middle Easterners, Caucasians, “everyone the same. They are my patients.”

His first COVID-19 patients were in their?70s and 80s, but now they are younger people, in their 20s and 30s.

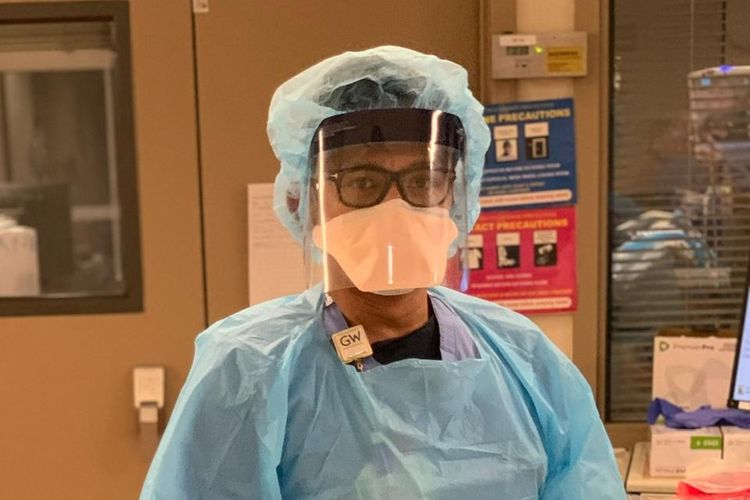

Adam Conners is a nurse from Indonesia

Adam Conners is a nurse from Indonesia“It's really sad. It's really depressing,” Conners said. “And when I go out from work, when I (leave) work, I see people in the street outside … not wearing masks or they're just not doing social distancing. … it (breaks) my heart.”

If only those on the street could “see inside of this hospital, people … dying,” said Conners, who would like to return to Indonesia to work with a local clinic, build?an outpatient clinic?and “try to help my people.”